Federal Circuit Misses the Mark on Design Patent Non-Infringement

- February 12, 2026

- Snippets

Practices & Technologies

Design Rights Litigation & Appeals Patent Portfolio Management Medical Device & Diagnostics Opinions & CounselingOn February 2, 2026, a divided Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed a district court’s grant of summary judgment of non-infringement in Range of Motion v. Armaid. Judge Tiffany Cunningham, joined by Judge Todd Hughes, authored the majority opinion in which the Federal Circuit held that no reasonable jury could find the design of Armaid Co.’s (“Armaid’s”) Armaid2 massaging device substantially similar to the design claimed in Range of Motion’s (“RoM’s”) Design Patent No. D802,155 (the “D’155 patent”), titled “Body Massaging Apparatus.” In our opinion, Chief Judge Kimberly Moore had a better take on the case. She noted in her dissenting opinion that a reasonable jury could find infringement, and, more importantly, the district court erred when it took this question away from the jury and granted summary judgment of non-infringement.

Background

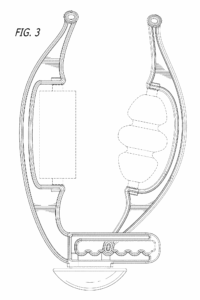

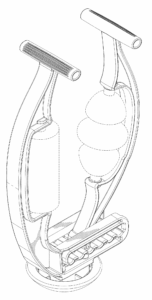

Armaid started selling its Armaid1 product, a massaging apparatus for the arms, in the 1990s. (See Armaid1 image below). In 2016, Terry Cross, the late President of Armaid, Nic Bartolotta, and Brian Stahl, the then and current CEO of RoM, formed RoM for the purpose of developing and selling the Rolflex. On May 25, 2016, RoM filed a design patent application (naming Terry Cross as the sole inventor). The patent issued as the D’155 patent on November 7, 2017. (Figure 3 from the D’155 patent is shown below.) RoM did not file any additional design patent applications to protect the visual appearance of its Rolflex product. In 2019, after a falling out between Mr. Cross and RoM, Mr. Cross renewed his focus on Armaid, which launched its Armaid2 product in late 2020. In late 2021, Mr. Cross died in an accident. Months later, on April 8, 2022 RoM sued Armaid in the District of Maine, alleging that Armaid infringed the D’155 patent by making and selling its Armaid2 product. (See below for an image of the Armaid2.)

The district court granted summary judgment of non-infringement, finding that no reasonable jury could find the Armaid2 design to be substantially similar to the design claimed in the D’155 patent. RoM appealed using two main arguments: (1) that the district court had erred in its analysis of the D’155 patent by eliminating entire structural elements from the claimed design; and (2) that, even if the district court’s claim construction is correct, the two designs are substantially similar.

The Federal Circuit’s First Mistake: Factoring Out Functional Elements

RoM’s first argument was that the district court improperly eliminated entire aspects of its claimed design, contrary to Federal Circuit precedent such as Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., Inc. In this case, the Federal Circuit rejected a district court’s claim construction because “it eliminates whole aspects of the claimed design.”

The Federal Circuit rejected the assertion that the drawings in a design patent constitute dispositive evidence that a given element is purely functional or ornamental, indicating that such a ruling would “render meaningless the ‘helpful’ practice of distinguishing between functional and ornamental aspects of the design.” Furthermore, the majority pointed out that RoM’s own marketing materials for the Rolflex characterized the arms of their product as functional, noting that the “clam-shaped roller arms” provided “significant leverage.” Due to these reasons, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court’s identification of the shape of the arms in the D’155 patent as functional was not erroneous.

The Federal Circuit’s Second Mistake: Taking the Decision Away from the Fact-Finder

RoM’s second argument was that, even if the district court’s claim construction were to be considered “somehow correct,” there remains a highly fact-dependent analysis of infringement that should be reserved for a jury, and, further, the designs are similar enough to withstand summary judgment of non-infringement. RoM argued that “one need only lay the pictures of the two designs next to each other” to find sufficient grounds to avoid summary judgment. The Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that this approach would “dramatically increase the scope of design patents . . . whenever functional considerations result in two designs sharing similarities.” The Federal Circuit indicated that such an approach would oversimplify the “ordinary observer test” to eliminate the step of claim construction, which appears to include factoring out functional aspects of the design. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s holding that the design of the Armaid2 product and the “narrow design” protected by the D’155 patent are “plainly dissimilar.”

The Dissent—A Better Take on the Issues

Chief Judge Moore began her dissent by stating, “the district court erred when it took this question away from the jury.” The rest of the opinion focused on what she believed to be part of an “easily solved problem that led the district court astray,” which “has infected several of [the court’s] cases.”

The dissent focused on the language used by the district court and the Federal Circuit when applying the “ordinary observer test” for design patent infringement, which originates from the 1871 Supreme Court case Gorham Co. v. White. The “ordinary observer test” asks whether the patented design and accused design are substantially similar in overall appearance as perceived by a hypothetical ordinary observer who is familiar with the designs in the prior art. Judge Moore argued that the court has “without realizing it, . . . meaningfully changed the substantial similarity test.” By shifting the verbiage from “substantially similar” to “sufficiently distinct” or “plainly dissimilar,” the Federal Circuit has changed the frame of reference in the legal inquiry. “The former causes the fact finder to focus on the similarity of the overall designs whereas the latter forces the fact finder to focus on the differences.”

Judge Moore contended that this shift and its effect on the framing of the legal issue contributed to a “trend in design patent cases” where the Federal Circuit had affirmed several district court findings of noninfringement by applying the “ordinary observer test” with the framing provided by the “plainly dissimilar” wording. She noted that the court reached its conclusion by focusing on differences in individual features rather than similarities of the overall designs, and that this was caused by a skewing of the legal frame of reference, which infected the analysis. “Could the framing ‘plainly dissimilar’ rather than ‘substantially similar’ have impacted the outcome?” she asked.

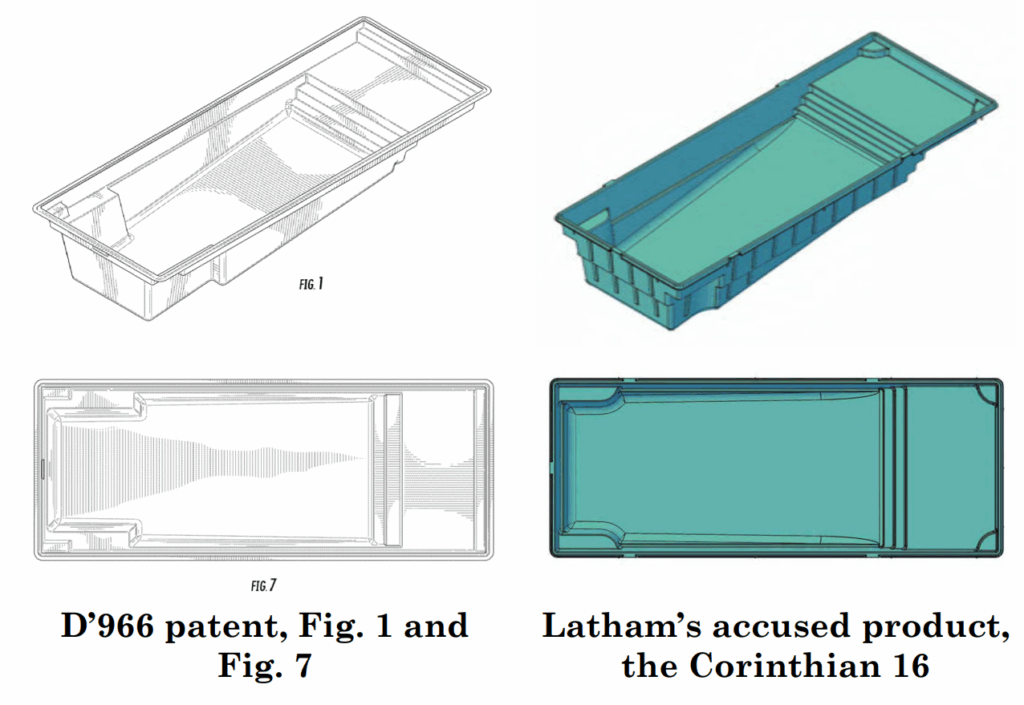

Judge Moore expressed concerns that this finding is representative of a much broader trend, citing the example of the Federal Circuit’s 2025 decision in North Star Tech. v. Latham. In North Star, as in the present case, the Federal Circuit affirmed a grant of summary judgment of noninfringement. In North Star, the Federal Circuit held that the claimed and accused pool designs (shown below) are “plainly dissimilar” as a matter of law.

Judge Moore stated, “It is hard for me to look at the patented pool design and the accused product and agree that no reasonable juror could find that their overall appearance is substantially similar.” Judge Moore concluded by advocating for refocusing the sole test for design patent infringement on substantial similarity, as set forth in Gorham.

A Troubling Opinion

The majority’s opinion is troubling here. It threatens to bring back the absurd situation in Richardson v. Stanley Works where portions of a design are factored out because they are “functional.” The Federal Circuit subsequently distanced itself from the language of Richardson in later cases like Apple v. Samsung (stating, “the claim construction in Richardson did not exclude those [functional] components in their entirety.”), Ethicon v. Covidien (“the district court’s construction of the Design Patents to have no scope whatsoever fails to account for the particular ornamentation of the claimed design and departs from our established legal framework for interpreting design patent claims.”), and Sports Dimension (stating, “in no case did we entirely eliminate a structural element from the claimed ornamental design, even though that element also served a functional purpose.”).

Articles of manufacture protected by design patents are by their very nature functional to at least some degree—if they lacked function altogether, design patent protection would not be available for the articles of manufacture. If a design is instead solely dictated by function, then the design is not ornamental at all, and thus may not be protected by a design patent. In the present case, as in many of these cases, we are dealing with designs that are somewhere in the middle; designs that are both functional and ornamental. A design patent may be construed without needing to “factor out” functional elements of the design. And this design patent claim construction may be narrow without needing to resort to “factoring out.”

The other concern is cogently explained by Judge Moore. Fact-intensive questions about infringement (or lack thereof) are being taken away from the fact-finder. Even if the result were to be the same, there is a worrying trend of design infringement being decided on summary judgment in situations where there remain substantial questions of fact.